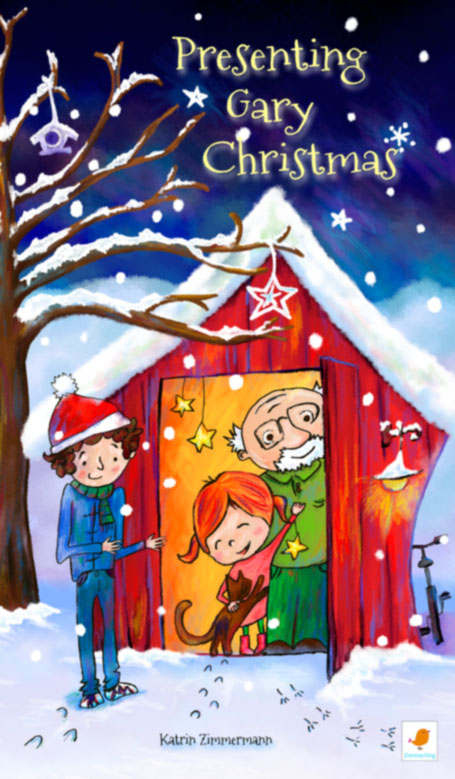

Presenting Gary Christmas

Thirteen-year-old Jendrik is annoyed – by his parents, his younger sister, and the stupid, never-ending, and irritating chores he has to do around the house. One day, while taking out the rubbish, he comes across another person who wants to make his life even more difficult. He finds a grandpa – not Jendrik’s own – sitting in their shed, claiming to be Father Christmas. Great – that was the only thing missing in Jendrik’s life!

But it’s no good – if he wants to get rid of the strange old man, he’ll have to help him …

A Christmas story to read to oneself or aloud to grumpy brothers, feisty sisters, and parents who should take out the rubbish themselves once in a while – it could just be worth it!

Charming, caring, and cheeky – presenting Gary Christmas!

Chapter 1

Translated by Clare McEniery

‘Yeah, yeah, I'm doing it.’

Annoyed, Jendrik tugged straight his blue down

jacket and slammed the door of the wardrobe shut. He

pulled his red beanie over his brown hair, which

looked scruffy even before putting on the woolly

Christmas present from Grandma Christa. He

stomped into the kitchen and, huffing, tore at the bin

liner to lift the stupid and overfull sack out of the

way-too-small bin.

‘For goodness sake, Jendrik. Why don’t you take

the rubbish bag out of the bin before putting your

boots on?’ His father shook his head in dis

belief. ‘Look at the kitchen floor. Now your mother will

have to mop it again.’

Joachim Oltmann yawned, scratched the thick hair

on the back of his head and – as he did each morning

on the weekend – disappeared with a mug of coffee

and the newspaper into the living room.

Jendrik stepped outside into the cold and let the

door slam shut behind him. He pulled the rubbish

bag, which threatened to rip with every step, past the

kitchen windows and laundry door to the back of the

house. In disgust, he lifted the grey lid of the rubbish

bin with the number ‘28’ on it and balanced the plas-

tic bag, through which he could see rinds of cheese,

tea bags, and scrunched up tissues, on top of all the

other rubbish bags. He pushed the lid down,

attempting at least to reduce the gap between it and

the bin, which would not close completely. He hated

touching the wet handle. It was gross when his finger-

tips came in contact with the liquid. Was that really

just rainwater? Disgusting! It was probably fetid water.

In summer, it was even worse. You never knew what

was waiting in the grey pit of the bin. From furry

mould to maggots of different colours and sizes

– everything was possible. Why was he the one who

always had to do the dirty chores? He was sick of it.

As soon as his sister got through her first day of school,

he would see to it that she did her part in the house.

Just because she was a few years younger than him,

she could wrap her parents around her little finger and

get away with anything. And she liked using this

abundance of free time to grate Jendrik’s already taut

nerves. She left her stupid ponies and dolls lying all

over the house, meaning you could be poked in the

behind by a doll’s foot or horse’s hoof if you sat down

to relax on the sofa with the console. All those

Spotties, Brownies, and Black Beauties – he would

have liked to throw them in the bin! They all looked

the same anyway. He just had to wait until summer

and the start of school – then he’d make some changes

as the older brother in the Oltmann family.

A quiet bump snapped him out of his thoughts.

Had that sound come from the shed? Jendrik looked

over at the red wooden door. It was locked. He glanced

at the window to the living room. His father was now

reading an edition of ‘National Geographic’ about

active volcanoes. It couldn’t have been his mother

either, as she was up in the attic, from where she had

threatened him with a football ban if the stinking bag

of rubbish didn’t immediately disappear. And Clara?

She was sitting in the bath with her herd of Schleich

toy horses. There it was again! That bumping noise. Probably

just a cat ... or probably not? How would a cat have

got into the shed? They really only used the shed in

summer. During winter, all the garden furniture and

the lawn mower were stored in there. And an old re-

frigerator. Cautiously, Jendrik approached the little window

on the side of the shed, next to which the bicycles

were stored under a roof. All was dark in the shed. He

could hardly make anything out. He moved even

closer and peered further inside. Bump! Again, the

noise! But there was nothing to see. It was most

certainly an animal that had trapped itself inside.

Maybe a hedgehog wanting to hibernate for the

winter. Or a confused owl searching for an escape.

Well, he would help free the poor creature. Jendrik

turned around, moved towards the door and

– ready to assist –

opened it and came face to face with an old man.

‘Whoops,’ said the man and ducked his head

quickly between his shoulders. ‘I probably was a little

too loud there. Good morning!’ He settled himself

back in to his deckchair slowly.

Jendrik stared wordlessly at the man in the green

coat.

‘Could you close the door, please? There’s a

draught.’ The man with the grey - white beard and blue

eyes gave Jendrik a friendly smile.

‘What?’ Jendrik held his gaze on what he had ex-

pected to be an owl and wasn’t sure whether he should

be afraid or annoyed.

‘The door, Jendrik. Please close the door so that it

doesn’t get even colder in here.’

Without taking his eyes off the strange fellow,

Jendrik closed the door. ‘How do you know my name?’

‘I’m Father Christmas. I know all children by

name.’ The old man smiled and motioned to the

garden chair next to him. ‘Take a seat. It’s your chair,

after all.’

Jendrik took one step closer and stretched his arm

out so he could grab the chair by its back and pull it

to him. He sat down on the very edge of the seat.

‘What are you doing here?’ he heard himself ask.

‘I’m waiting for my people. Well, for my reindeer.

But first, one of my angels has to find me. Or one of

my elves. I know I can’t count on the gnomes. They

don’t like leaving the North Pole.’

‘Gnomes? Angels? Elves? Aha.’ Jendrik stood up

slowly. ‘So, my parents probably wouldn’t be thrilled

with you making yourself at home in here. Why don’t

you shove off somewhere else?’ He made for the door,

without taking his eyes off the old man. Even though

the old man was polite, you could never know if

someone like this was going to flip out and knock you

down from behind. ‘I’ll be going then.’ Jendrik stood

with his back to the door, his hand resting on the

handle. ‘Alright, well, as I said, see you.’

‘I can’t leave. I’m sorry.’ The unwanted guest

shrugged his shoulders. ‘Oh, and unfortunately

neither can he.’ He motioned to the shelf on the wall

behind him. Jendrik couldn’t quite make out what

was lying on the checked cushion, but it looked like a

fluffy, brown pillow and was round like an advent

wreath.

‘What the heck is that? Did you bring a giant rat

along with you?’

‘No, those things never travel alone. That’s my cat.

Before I left, he sneaked into my luggage without my

knowledge. He had no idea we’d be stranded here and

unable to get back to the North Pole.’

Annoyed, Jendrik rolled his eyes. Today was

turning out to be just great.

He sighed. ‘Okay, if you really think you’re the

funniest joke at the craziest

time of the year, then surely you realise today is the

eighteenth of December. So, you should get cracking

on handing out the presents, okay? As I said, see you

later. And take your lice - ball up there with you.’

‘That’s just my problem. Time is slowly running

out.’ The old man drew in a breath through clenched

teeth, so that it made a hissing noise. Jendrik’s father

did the same when things got awkward at the car

mechanic because the amount on the bill was not to

his liking. ‘But maybe you can help me, Jendrik. Then

you’ll be rid of me faster.’

When he spoke, the man didn’t sound as old as he

looked. But he was obviously not right in the head.

‘The good thing about helping me is that then I’ll

have time to put your new bike under the tree.’ He

glanced at Jendrik over the rim of his glasses. ‘By the

way, a nice sort of tree you’ve picked out for your-

selves. I like it. Especially the colour. Pure green. No

blue tones. This year it definitely won’t clash with the

green carpet you always lay underneath.’

Jendrik considered a moment. They really had put

a green mat under the tree every year to catch the fir

needles and candle wax. And last year they really did

have a tree that looked more blue than green. Dad had

chosen it himself, and Mum could barely contain her

anger about the blue tone of the tree. She said the

colours clashed – green and blue definitely shouldn’t

go together, and the red baubles looked tacky in its

blue branches when they were supposed to look

traditional. Clara had added fuel to the fire by singing,

‘Green and blue, looks like poo–’

‘Clara!’ Their father had chided her.

But, as always, Clara had to push it too far.

‘–Redbaubles on it, make me vomi–’

‘I mean it–that’s enough!’ Dad rounded on her, not

so much because of the naughty words, but more be-

cause he was afraid of Mum’s bad mood.

‘Then we’ll just use the gold stuff and that’ll be the

end of it,’ Dad said in an annoyed voice, probably

hoping the discussion would end with that.

But the gold baubles wouldn’t work either, in

Mum’s opinion. Because of the blue, instead of

looking warm and festive, they would look pee

-yellow. At this, Dad threatened to hack the tree to

pieces there and then, if Mum didn’t stop over

-reacting. Then Clara started to cry and didn’t stop for

ages. No one wanted to go through that again. For that

reason, this year, Mum and Dad decided to get the tree

together, with Clara, from the local Christmas market.

Of course, no one asked Jendrik, as usual. Not that he

cared. It wouldn’t have been any fun anyway, waiting

– most likely in the rain–for Mum and Dad to agree

on which dead tree should be shoved into a net. After-

wards, he would probably be the one who would have

to drag it home on his own, while Clara, as always,

would be carried home, holding both her parents’

hands and running up and jumping on the count of

three. They would return to a dark house because, as

soon as Mum had won the battle against the knotted

fairy lights and laid them like looted bounty on hooks

in the windows, no one was allowed to turn on any

other lights. Not even while they were eating. This was

so everyone could see the pretty lighting. As it was,

the teeny tiny lamps lit up little more than the fact

that, on each string of lights, at least a handful of light

bulbs were blown. It was dark in the Oltmann house,

pitch black. You could hardly even tell what was on

your own plate.

Jendrik eyed the old man sceptically. ‘Tell me. Are

you one of those crazy people who spyon others in

the dark through their windows?’

‘Looking through windows: yes. Crazy: no. After

all, I have to check when people are busy and won’t

see me, so I can lay the presents under the Christmas

tree. Because you all go to church each year, that

makes my job a great deal easier. These days, a lot of

people stay home, unfortunately. In that case, it is

often a real balancing act not to be discovered. Well, I

guess in all jobs, nothing gets easier, even in mine.’

Jendrik thought for a moment. That comment

about going to church was also true. The old man

should be starting to creep him out by now.

‘If you really are Father Christmas, then why don’t

you want to be discovered? Father Christmas gives

presents to children who recite poems about nuts and

punishes those who have been bad. So most children

like him. And for those who don’t like him, the par-

ents are happy that their snotty little kids get a smack

on the bum for being naughty.’

‘That’s a load of nonsense. But that’s okay. The peo-

ple who say such things about me have never seen me.

I would never hurt a child and I never heap Christmas

presents on anyone. I give presents to those children

whose parents really need my help.’

‘Hmm ...and what’s with all the secrecy?

Why are you hiding yourself?’

‘Again, wouldn’t you rather just take a seat?’

‘No, I have football practice soon. You know what?

Whatever it was that made you end up here, please

just move yourself on. My father has a heart attack

when the neighbours’ dogs stray into our garden and

leave dog poo behind. If he finds you here–’

‘I’m not going to poo in your garden.’

‘Jeeendriiiik!’ his mother’s voice rang from near the

front door. ‘Tom’s here. Get a move on!’

‘Sorry, I really have to go now.’ Jendrik stepped

backwards out of the shed, and the bearded man with

the clear eyes nodded in understanding.

Tom, Jendrik’s friend and neighbour, hopped

nervously from one leg to the other. ‘Hurry up! Didn’t

you hear the honking? Old Mum’s getting annoyed.’

‘Sorry, I had to slave away here at home!’ Jendrik

excused himself, sounding more exasperated than he actually felt.

His mother raised her eyebrows in disbelief. ‘Oh, is

that so?’ Without waiting for an answer, she held his

packed black sports bag out to him on his way to the

front door. ‘A pleasure, my son. And next time, you

can pack it yourself, okay?’

Two hours later, Jendrik opened the gate to his house,

and raised his hand once more to say goodbye. He’d

had at least three chances to score a goal during

training and he’d stuffed them all up because the

strange fellow in the shed kept playing about in his

head. Hopefully he had disappeared now.

Just as Jendrik was about to press the doorbell, he

stopped. Should he go and take a look? He pulled his

hand back and sneaked past the kitchen window to

the garden around the back. As he stood in front of

the shed door, he hesitated. He could just tell his father

– he would certainly bundle the guy out!

But his curiosity was stronger than his doubts

about the truthfulness of the Father Christmas story.

He pushed the door handle down carefully. His heart

pounded ... He opened the door a crack ... Nothing.

The chair was empty. He opened the door the whole

way. No one there. Phew! Everything looked as it

always did: the deckchairs in the middle, the old re-

frigerator to the left, the mower to the right, the

shelves on the back wall, the outdoor table folded up

against them. There was no sign of the cat either.

Everything was okay. He could go ... But wait! His

blue thermos bottle was on one of the shelves. How

did it get there? What had his Mum ranted? That he

needed to look after his possessions better, that she

couldn’t be constantly buying things again, just be-

cause he was careless and always losing them. He pro-

tested multiple times that he hadn’t lost the bottle,

but of course she hadn’t believed him.

Jendrik grabbed the bottle from the shelf. But there

was something still in there. It was probably some old

Gatorade. Urgh! It would be best if he placed the bottle

somewhere so his mother would find it.

Then thechance of her finding it and getting rid of the floating

bits of mould would definitely be higher ...

Suddenly, the door opened. Clara was about to slip

inside when she spied him. She gave such a start that

it sent the tin cups in her red picnic basket rattling.

‘What are you doing here?’ he asked harshly.

‘Nothing. And you?’ For a six-year-old, Clara was

very quick. You had to keep an eye on her. With her

small basket on her arm, she glared at him like a

vicious Little Red Riding Hood, who could take on

any wolf.

‘I only came to get my bottle.’ He tossed his newly

found object casually into the air. He was about to

catch the bottle again, when he suddenly cried out.

‘Ouch! Oh, man!’ Steaming liquid flowed over his

right hand, which he clasped with his left, while the

open bottle fell and rolled across the floor. The back of

his hand was bright red. ‘What the heck! Why on earth

is there hot water in there?’ he hissed.

Clara didn’t say a word. She opened the fridge,

grabbed something from inside the door and slapped

a blue ice pack on her brother’s burning hand.

‘Oww!’ he snarled at her, but continued to hold the

ice pack on the scalding spot. As Jendrik looked up, he

couldn’t believe his eyes:

the refrigerator was packed full of food. Perfectly

stacked, like in a supermarket, were Petit Miam

yoghurts, teddy-bear-shaped salamis, cream cheese,

jam, grape juice, milk, and a cucumber. Clara pushed

the door shut quickly.

‘Hang on–are you crazy? What’s all that about?’

Jendrik stared at his sister.

‘What?’ Clara held his accusing stare.

‘Why are you stocking up a private store here?’

‘It’s not my stuff. It belongs to Daddy.’ She looked

at him defiantly.

‘Oh sure. Petit Miam and milk! I’m not stupid, you

little thief! And what’s in there?’ He nodded in the di-

rection of the picnic basket. ‘Pinched something else,

have you?’

He grabbed the basket by the handle, but Clara’s

hands gripped it tight.

‘Let go, you trickster!’ he growled.

‘No, you dumb-bum!’ She pulled the basket to-

wards herself. Just as she was about to bite him on the

hand, a thunderous noise bellowed through the shed.

‘Enough!’

The fighting pair jumped. Puffing, Jendrik let go of

the basket,

which Clara was still holding in a tight em-brace.

Jendrik couldn’t believe what he was seeing: it

was the self-proclaimed Father Christmas from that

morning, suddenly standing beside the two of them.

‘Clara, let it go,’ said the old man gently and laid a

hand on the little hothead’s shoulder. ‘It’s very nice

that you’re going into battle for me, but I don’t want

any fighting. And certainly not on my account.’

Jendrik couldn’t believe his eyes or his ears. ‘You

know him?’